October 2022 Fine Arts

Paris, la nuit (Paris at Night)

The Kaleidoscopic Portrait of a Modern City

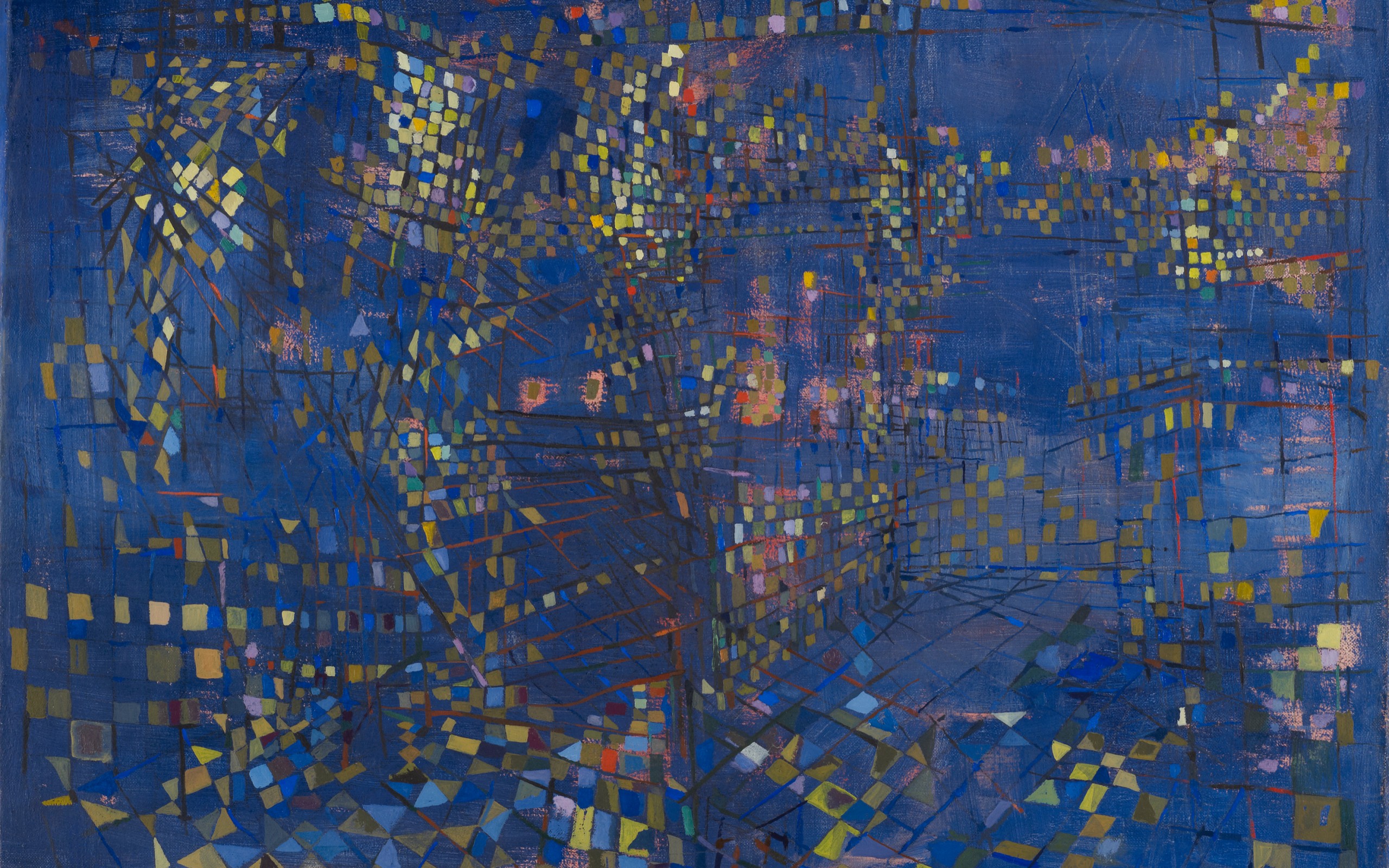

The aim of an admirable small work painted by Maria Helena Vieira da Silva in 1951 was to depict the City of Light at night. The painting is included in the exhibition “Paris et nulle part ailleurs”1 (Paris and Nowhere Else) which has just opened at the Musée de l’Histoire de l’immigration in the city. Its inclusion is a reminder of the attraction and fascination of the French capital that, in the post-war period, was rediscovering its aura, celebrated by the many foreign artists who flocked to the city on the Seine.

See the artwork in the collectionMaria Helena VIEIRA DA SILVA (Lisbon, 1908 – Paris, 1992)

Paris, la nuit (Paris At Night)

1951

Oil on canvas

54 x 73 cm

FGA-BA-VIEIR-0002

Provenance

Private collection, Paris, 1988

Fine Art Consulting Service LLC, Albany (New York), 2008

Paris rediscovered

Without the title of the work for reference, it is difficult to recognise this fragmented mosaic of electric tesserae as a night view of the French capital. Once it has been identified, however, the eye, initially disoriented, instinctively tries to reassemble the parts of the disjointed puzzle. The viewer’s imagination can then set out and wander through the busy streets of Paris by night. From 1938, Vieira da Silva lived in a studio flat at 51 Boulevard Saint-Jacques, not far from the vibrant nightlife of Montparnasse. Ten years earlier, the Portuguese artist had moved to the world’s art capital to round off the training she had begun in Lisbon, her hometown. Eager to gain experience and knowledge, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–1992) attended various private art academies in Paris.2 It was on the benches of the Grande Chaumière academy3 that she met her future husband, the Hungarian painter Árpád Szenes (1897–1985), in 1928. Both had left their home country to settle in “a cosmopolitan and relaxed environment where we created and lived in freedom, surrounded by friends who mostly also came from elsewhere”.4 One such artist was the Uruguayan Joaquín Torres-García (1874–1949), whose paintings Vieira da Silva discovered in 1932. Many of her later works reflect this decisive encounter. From Torres-García she adopted the grid-like organisation of the pictorial space (fig. 1), in accordance with a method derived from Cubism, which she would subsequently seek to deconstruct.

The first change in her style was triggered by the dramatic events of World War II that were tearing Europe apart. Árpád Szenes, who was of Jewish origin, felt threatened. The couple were compelled to leave Paris for Lisbon, from where they sailed to Rio de Janeiro in June 1940. Following their return to the French capital in March 1947, Vieira da Silva exhibited her Brazilian works at the Galerie Jeanne Bucher.5 One was Le Désastre (The Disaster), a genuine “cry of the absurd”6 for its author (fig. 2). “Afterwards, I realised that I could no longer continue in that way,” she explained, who thereafter wished to “give joy”, and leave to others the possibility of “showing horrors”.7Painted in 1951, Paris, la nuit is one of the works representative of this turning point. It is also one of the most striking contemporary depictions of the metropolis, which was itself undergoing transformation, at the start of the 1950s.

Vieira da Silva left Brazil “to fulfil her Parisian and international destiny”.8 Back in the French capital, she connected once again with her friends and steadfast supporters from before the war, primarily the gallery-owner Jeanne Bucher, who exhibited her work once more in 1951.9 That same year, the equally distinguished Galerie Pierre offered Vieira da Silva a second solo exhibition.10 It was in this creative ferment that Paris, la nuit was created. The painting was not painted sur le motif, but in her studio on Boulevard Saint-Jacques. She always composed her works from memory, in an attempt to reproduce on canvas the impressions made on her while wandering through the city. “Do not paint objects, but the effect they produce”,11 recommended Stéphane Mallarmé. Vieira da Silva applied this precept to Paris, la nuit, as she did to all the portraits of cities, whether existing or imaginary, that she produced after World War II. The urban landscape became one of her favourite subjects, especially since it accorded perfectly with her pictorial research into perspective, planes and lines.

“Do not paint objects, but the effect they produce”, recommended Stéphane Mallarmé. Vieira da Silva applied this precept to Paris, la nuit, as she did to all the portraits of cities, whether existing or imaginary, that she produced after World War II.

New spatiality

Indicating renewal, Vieira da Silva’s city becomes a perpetual worksite. Streets, residential buildings, urban furniture, tram cables and overhead metro lines, “everything is reduced to a scaffolding of intersecting lines”.12Their tangle creates a tightly woven net, like the sprawling network of traffic routes in the then expanding Parisian metropolis. This iron lattice that spans the capital traps the city lights and, with them, the viewer’s gaze, drawing it to zones where the mesh even disappears from time to time, swallowed up in the darkness of the night. This phenomenon of headlong perspective sweeps the gaze from one end of the composition to the other “in a swirling vortex”.13 Intoxicated by this transport, the observer becomes lost in the delicate ghostly architecture of Paris, la nuit. “It is there that Vieira da Silva’s eye travels, in the silence of the voids and then the clash and fracture of the lines”.14 Her “cyclonic and prismatic eye”, the creator of “a visionary painting”, in the words of Guillaume Theulière, invents a new spatiality with shifting contours like “a labyrinth in constant expansion”.15

Fragmentation of the real

Vieira da Silva’s cities are as extensive and teeming as her mental landscape allows. Like thoughts, they are constantly in motion. To depict this permanent instability, she methodically fragmented the space. Beginning in the 1930s, she employed a diamond pattern to facet her compositions. The famous painting La Machine optique (The Optical Machine) of 1937 (fig. 3) attests the early use of this repeated motif that allowed her – as Op art would systematize it later – “to introduce mobility within the pictorial matter itself”.16 Like jewels in their settings, the diamonds reflect the light like the azulejos that lined Vieira da Silva’s childhood memories. In Paris, la nuit, they mirror and multiply the lights of the modern city, like those of the neon shop signs that began to reappear after the blackout of the war.17 The seemingly disorderly repetition of the electric lozenges echoes “the sounds and chatter of the urban setting”.18 It is also the instrument, one might say the key, used by Vieira da Silva to open up new perceptive possibilities which, at that time, were not unrelated to cinema. The link with the seventh art has been underlined by Daniel Abadie, who notes that, in the fixed image of the painting, the artist integrated “the very principles of cinematographic vision: high- and low-angle shots, zooming effects, tracking, panoramic shots, etc.; even the breaks in perspective can be compared to sequential shots, since in both cases an active gaze is involved”.19 In the maze-like space of Paris, la nuit, the moving eye, lacking landmarks in the darkness, instinctively seeks the reassuring light of the boulevards. It is there, at the junctions of the major roads, that the ballet of luminous letters dances to the rhythm of Eugène Deslaw’s (1898–1966) Nuits électriques (Electric Nights). This experimental film made in 1928 (fig. 4), followed in the 1930s by the night-time photographs of Man Ray (fig. 5) and Brassaï, illustrates the immediate appeal of the capital’s new face, illuminated by incandescent light.

Electric nights

The light of progress is the enemy of the darkness of night. In Paris, la nuit, the sky is eclipsed by the halo of public lighting. Without waiting for this to become commonplace, artists strove to capture the new appearance and atmosphere of their living environment. The illuminated city offered a new plasticity whose artistic value was recognised at the end of the 18th century by Nicolas Restif de Le Bretonne (1734–1806). In his astonishing nocturnal wanderings (Les Nuits de Paris), the writer fell under the spell of “the glow of street lamps”, which, according to him, did not destroy the shadows but, on the contrary, made them “sharper”, recognising in this metamorphosis “the chiaroscuro of the great painters!”20 Among them, William Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) was the first, around 1870, to make the night a real pictorial experience, of which infinite variations have since been produced. Paris, la nuit is one of those created in 1951, together with Amédée Ozenfant’s Une rue, la nuit (Street at night, fig. 6) and Eugene Bennett’s Night Lights (fig. 7). The differences between these various nocturnal visions points up the outstanding originality of Maria Helena Vieira da Silva’s art, whose poetry transports us beyond reality, to where the imaginary begins.

Bertrand Dumas

Curator of the Fine Arts collection

Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, October 2022

Notes and references

- “Paris et nulle et ailleurs, 24 artistes étrangers à Paris de 1945 à 1972”, Paris, Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration (Palais de la Porte Dorée), 27 September 2022 – 22 January 2023. Curator: Jean-Paul Ameline.

- After the Grande Chaumière, where she briefly attended the courses given by Antoine Bourdelle, Vieira da Silva enrolled at the Académie scandinave where she studied sculpture under Charles Despiau, then painting under Charles Dufresne, Henry de Waroquier and Émile Othon Friesz. In parallel, she took evening classes in engraving at Atelier 17, directed by Stanley William Hayter. She also attended the Académie Colarossi and, lastly, the Académie moderne where she frequented the courses in applied arts given by Fernand Léger.

- Located at 14 Rue de la Grande Chaumière in the 6th arrondissement. The academy was founded in 1904.

- BAIRRÃO RUIVO, Marina, “Lisbonne-Paris, les villes de Maria Helena Vieira da Silva”, in THEULIÈRE, Guillaume (ed.), Vieira da Silva, L’œil du labyrinthe, exhibition catalogue [Marseille, Musée Cantini, 10.06 – 06.11.2033; Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 16.12.2022 – 03.04.2023] (Paris: In Fine éditions d’art, 2022), p. 36.

- “Les peintures de Vieira da Silva de retour à Paris”, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, 12.06 – 03.07.1947.

- Vieira da Silva, quoted in THEULIÈRE, Guillaume (ed.), op. cit., p. 95.

- Ibid., p. 95.

- BAIRRÃO RUIVO, Marina, op. cit., p. 37.

- Et puis Voilà. Histoire de Marie-Catherine, gouaches de Vieira da Silva, Galerie Jeanne-Bucher, Paris, 24.11.1951 (opening).

- Vieira da Silva, Galerie Pierre, Paris, 1951.

- MALLARMÉ, Stéphane, letter to Henri Cazalis, dated 30 October 1864.

- GOLDBERG, Itzhak, “Espèce d’espaces”, in THEULIÈRE, Guillaume (ed.), op. cit., p. 49.

- THEULIÈRE, Guillaume, “Vieira da Silva, L’œil du labyrinthe”, op. cit., p. 26.

- Ibid., p. 26.

- Ibid., p. 26.

- GOLDBERG, Itzhak, op. cit., p. 51.

- Neon lights were patented by the Frenchman Claude Georges. He installed the first neon shop light in 1912 on the roof of 14 Boulevard Haussmann with the aim of attracting passers-by to the hairdressing salon, Le Palais Barbier. Neon lighting had its heyday in the interwar period.

- THEULIÈRE, op. cit.

- ABADIE, Daniel, “Vieira da Silva, Lais et relais du regard”, in Vieira da Silva, exhibition catalogue [Paris, Fondation Diana Vierny-Musée Maillol, 03.03 – 13.06.1999; L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, Musée Campredon, 03.07 – 03.10.1999], p. 15.

- Nicolas Restif de La Bretonne, Les Nuits de Paris ou le spectateur nocturne (1786-1877) (Paris: Gallimard, “Folio classique”, 1986), pp. 33-34, own trans. Quoted in Gallais, Jean-Marie, “Se perdre dans la nuit”, in: Peindre la nuit, exhibition catalogue [Metz, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 13.10.2018 – 14.04.2019], p. 54.

Bibliography

BONET CORREA, Antonio. Viera da Silva (Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, 1980), col. repr. n.p., no. 42.

BUTOR, Michel. Viera da Silva. Peintures (Paris: L’Autre musée, 1983), listed p. 23, b/w repr. p. 45.

DE CHASSEY, Éric (ed.); NOTTER, Éveline (ed.); MOECKLI, Justine et al. Les Sujets de l’abstraction. Peinture non-figurative de la seconde école de Paris, 1946-1962. 101 Chefs-d’œuvre de la Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, exhibition catalogue [Geneva, Musée Rath, 06.05 – 14.08.2011; Montpellier, Musée Fabre, 03.12.2011 – 18.03.2012] (Milan: 5 Continents, 2011), quote p. 248, col. repr. p. [249] and listed p. 308, no. 84.

LASSAIGNE, Jacques. Vieira da Silva (Paris: Éditions Cercle d’Art, 1987), col. repr. p. 175, no. 199.

Lost, Loose and Loved: Foreign Artists in Paris, 1944–1968, exhibition catalogue [Madrid, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 21.11.2018 – 22.04.2019] (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2019), listed p. 253, col. repr. p. [63].

MANSAR, Arno. Nicolas de Staël (Paris: La Manufacture, 1990), quote p. 47.

ROY, Claude. Vieira da Silva (Hannover: Ars Mundi, 1988), col. repr. p. 17, no. 33.

Viera da Silva, monograph (Geneva: Skira, 1993), quote p. 339.