April 2022 Decorative Arts

Marriage Casket

Depicting couples in conversation, in codified stances full of restraint, this marriage casket made in Venice at the beginning of the Quattrocento will be on display starting on April 13, 2022, in the first room of the exhibition The Theatre of Emotions at the Musée Marmottan Monet (Paris). This dialogue with a collection of works from the 14th to the 21st century, tracing the history of emotions and their pictorial expression, is an opportunity to explore the secrets of how the chest was made and the breadth of its meanings.

See the artwork in the collectionEntourage of the Embriachi workshop

Marriage Casket

Circa 1400-1420

Venice

Bone, wood, “alla certosina” inlays (wood, bone, stained bone and horn)

15.6 x 20.2 x 11.6 cm

FGA-AD-OBJ-0077

Provenance

Sotheby’s London, December 4, 2013, lot 47

This quadrangular box, decorated with polychrome geometric motifs, boasts a frieze of bone plates on its walls. Carved in relief and fixed onto a wooden structure, they depict couples in conversation, in codified attitudes, imbued with restraint. The characteristics of this casket connect it to the very particular production of the so-called “Embriachi” workshop, active in Venice in the early years of the 15th century. They also relate it to a type of object that played an essential role in married life during the Renaissance: marriage caskets.

“Embriachi”: an original production at the turn of the Quattrocento

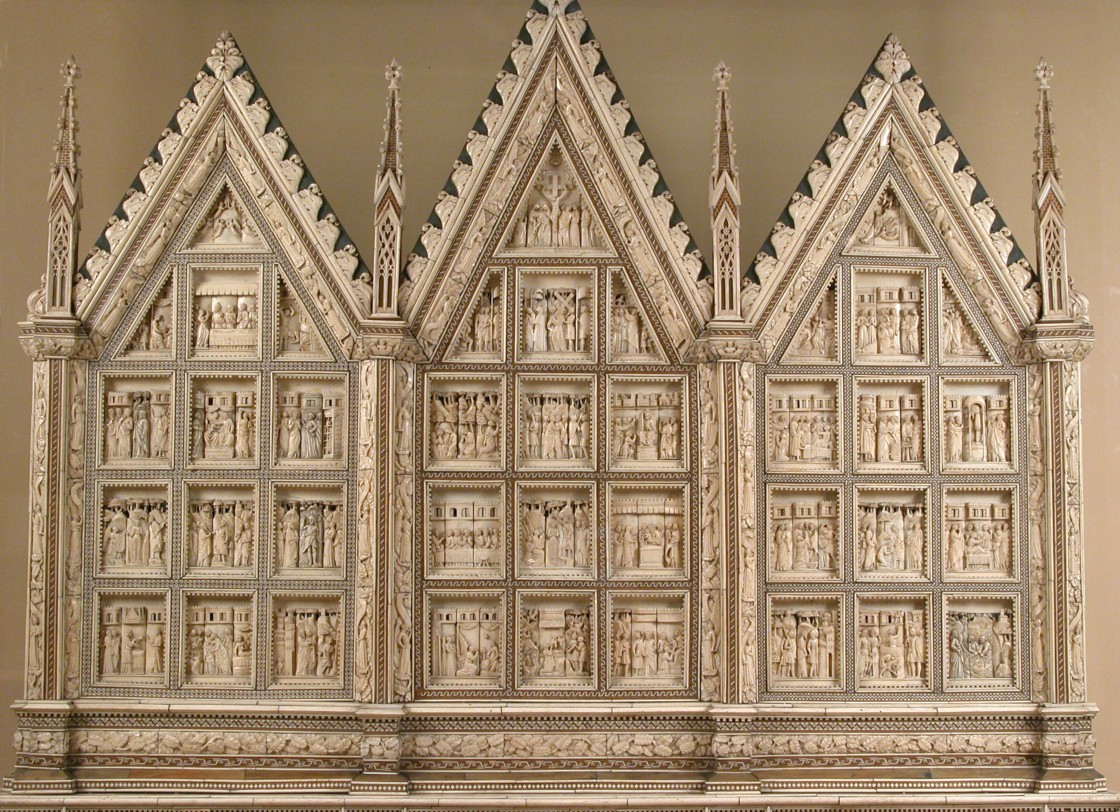

Today better known thanks to the extensive research work recently carried out by Michele Tomasi,1 this workshop owes its name to its founder and owner, the Florentine Baldassare Ubriachi (or degli Embriachi), a merchant and banker established in the Tuscan capital before he settled in Venice in 1395. Together with sculptor Giovanni di Jacopo, who directed the workshop, from the last years of the fourteenth century, Baldassare oversaw a production that was truly original, and still easily recognizable today, comprising monumental altarpieces and various objects, primarily triptychs and caskets. All were made from an assembly of bone plates sculpted in relief, set in polychrome marquetry frames with contrasting geometric motifs, a technic known as “alla certosina”, which were made from wood, horn and bone, partly stained green.

Offering an aspect as white, shiny, and silky as ivory, but at a lower cost and in much larger dimensions, Embriachi altarpieces contributed to the reputation and renown of the workshop all over Europe, particularly in Spain and France. The monumental triptych commissioned by Duke Jean de Berry for the Abbaye de Poissy, now on display in the Louvre Museum2 (Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. OA 125), that of the Abbaye de Cluny (The Metropolitan Museum of Artfig, New York, fig. 2) or the one housed in Pavia Cathedral are some of the most spectacular examples. Composed of approximately forty to sixty bovine or equine bone plaques, sculpted in relief and inserted into a structure reminiscent of Gothic-style architecture, they derive their value not so much from the material used as from the quality of the sculpture and the sophisticated refinement of the marquetry inlays.

Alongside these creations intended for prestigious sponsors, portable triptychs, of varying sizes, offered a reduced and more accessible version, intended for a less demanding clientele, made up of bourgeois families and merchants. The one that features in the collections of the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, some thirty centimetres high, consists of two articulated shutters and represents a Virgin and Child surrounded by saints surmounted by a crenelated urban landscape (fig. 3), and is emblematic of this production.3 The slightly lesser quality creations to which it belongs nevertheless contributed to the success of the workshop, whose production was more than likely imitated by anonymous emulators.

The caskets, hexagonal or rectangular, surmounted by a lid decorated in several registers and fitted with a metal handle—missing on the exemplar of the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art—constitute the secular, albeit equally renowned component of the workshop’s production, in addition to mirror frames and various everyday objects.

The signs of pre-industrial organization

A comparison of the multiple triptychs and caskets housed in different public collections has highlighted the presence of recurrences and variations in the use and combination of the plates composing these objects. These observations have allowed us to better understand the methods of fabrication and the organization of production within the workshop.

The latter was based on two concepts that underlay pre-industrial production: standardization and modularity,4 thanks to a distribution of skills according to the different phases of fabrication. The wooden structure, the sculpture of the bone plates based on pre-established iconographic formats and diagrams, and even the realization of the marquetry motifs (in the form of ingots from which portions of the desired size were cut)5 were therefore entrusted to various specialized craftsmen, as were the assembly phase and the application of gilding and polychromy. This organization also offered the possibility of personalizing creations, thanks to the combination of the plates, the chosen story, and even the presence of the coats of arms of the sponsor and/or recipient, painted onto the shields of the casket lids.

On the casket conserved by the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, a particular phenomenon can be seen: each of the plates forming the decoration features two characters: visibly one female, to the left, and the other, male, to the right, all with subtly different attitudes. A careful examination reveals, however, that to the left of the lock, there is a plate with a design that is almost identical to that of the plate preceding it: the character on the right places his hand on the swollen enlarged abdomen of the character on the left, suggesting the announcement of a pregnancy (fig. 4). However, this plate has slightly different proportions from the others: a little shorter, it has been completed with a small bone wedge inserted just above. Its style is also a little different, as is the appearance of the characters, which are more massive in stature.

These elements lead to two conclusions. The plate located to the left of the lock was probably used to fill a gap in the initial frieze. Its existence also shows the repetition of iconographic formulae according to different formats, and potentially within the same workshop or several workshops.

It also reveals the partial reassembly of the elements carved onto a wooden structure, reinforced by the presence of small notches in the upper part of the other plates. (fig. 5), more than likely due to a previous assembly.6

A delicate attribution

Furthermore, the comparisons made by researchers between the different artefacts coming from the Embriachi workshop have made it possible to identify different qualities amongst the plates used. Under the direction of Jacopo, several active hands have been detected. The existence of several workshops contemporaneous with that of Baldassare Ubriachi was also likely: these workshops were more followers than competitors, and took advantage of the strong demand generated by the success of the “Embriachi” objects and the low-cost production solutions developed by Baldassare and Jacopo.

Therefore, within the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Paul Williamson and Glyn Davies have excluded several caskets from the Embriachi corpus. Amongst these, are two caskets similar to that of the Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, both in terms of the style and attitudes of the characters: one is hexagonal (cat. no. 274, inv. A.15-1956), the other rectangular (cat. n° 279, inv. A.22-1952, ill. 6 and 6 b).7

On these caskets we can see couples, dressed in long clothes with ample folds and wide sleeves, either at a distance, in conversation, or affectionately grasping each other by the arms. The gestures, present each time in only three variants, are not the same however, as the ones seen on the box belonging to the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art. The corner plaques show a single female figure, standing, armed with a spear and a large shield. However, the sculpted plates of the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art casket have more relief. The figures stand out more from the background and the folds of clothing appear softer.

All of these subtle variations reveal the delicate nature of attributing pieces to the Embriachi workshop or to those of its followers, calling for caution for these numerous productions, of which the casket of the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art is part. This is why it was deemed preferable to identify its provenance as within the entourage of the Embriachi workshop, contemporary with its activity.

Courtly iconography

We can distinguish two types of caskets within the corpus of secular objects appreciated by the middle and wealthy classes. Some tell a real story, linked to the literary culture of merchant society in Tuscany and northern Italy at the turn of the 15th century. Their iconography readily takes its inspiration from ancient literature: the adventures of Jason (fig. 8), those of Paris (Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. OA 125), or the story of Pyramus and Thisbe, all of which benefited from a certain success. The iconography also draws upon the cantari and madrigals dear to those familiar with the work of Boccaccio, Petrarch, and Dante. As Michele Tomasi notes, the choice of these stories allowed future spouses, bound by the gift of this casket, to identify with the heroes of famous love stories, flattering their ambitions, and showcasing their culture.8

Other caskets, like the one that forms part of the Foundation’s collections, represent simple couples in conversation. More sober, less demonstrative in terms of their sponsor’s culture, they nevertheless evoke certain values. The couple’s relationship is expressed through a series of restrained attitudes and codified or even stereotyped gestures, as is the case here: embraces, a hand placed on a round belly, or on the chest by the man or by the woman... gestures reproduced in several variants. At the end of the Middle Ages, and until the beginning of the Renaissance, the family was the privileged place where one learned to master a code of emotions9 governed by a whole system of values in which honour, in connection with marital fidelity, occupied an indispensable place.

A wedding present

In both cases, the iconography used on the walls of these caskets is closely linked to the function of the objects, and were part of the abundant rituals surrounding marriage ceremonies in 15th and 16th century Italy.

Until the Council of Trent, marriage in Italy was an institution devoid of legal consistency. This is why opulent festivities, particularly in the Venice region, came to give it a tangible material existence.10 In this context, the gifts offered by the groom to his future wife played a special role. In the middle and affluent classes, once the marriage negotiations had been concluded, the actual courtship could begin. The groom gave his beloved a casket, decorated either with stucco reliefs (pastiglia), or with carved bone plaques, delivered in person by small children, considered talismans for the future fertility of the couple.11 The object often contained various gifts, many symbolic, such as a precious belt, alluding to the chastity of the young bride-to-be.12

Various inventories attest to the permanence of this custom throughout the 15th century: the dowry of Nannina de'Medici, married to Bernardo Rucellai in 1466 for example, included “two chests in inlaid ivory.”13 Yet, these caskets were not the only objects linked to marriage in Renaissance Italy: majolica also frequently played a role, as evidenced by the wedding vase from Deruta conserved by the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art. (fig. 10).

Particularly rooted in the customs of the peninsula, this practice also extended to other regions, and in other forms: in Baroque Germany, small ivory boxes celebrating the couple continue to be offered between engaged couples, such as this round box, also part of the collections of the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art (fig. 11).

The “Embriachi” type caskets often had several uses down through the centuries. They were sometimes used as boxes, or even reliquaries in church treasuries, despite their overtly secular iconography, before being appreciated by 19th-century enthusiasts as testimonies to Renaissance private life.14

Fabienne Fravalo

Curator of the Decorative Arts Collection

Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, april 2022

Notes and references

- Cf. mainly: Tomasi, Michele. “Baldassare Ubriachi, le maître, le public” in Revue de l’art, no. 34, 2001-4, p. 51-60 & Monumenti d’avorio. I dossali degli Embriachi e i loro committenti. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, & Paris, INHA, 2010 (French summary: p. 329-369).

- Tomasi Michele. “Le retable des Embriachi du musée du Louvre: datation, fonction, destination, iconographie” in La revue des musées de France. Revue du Louvre, 2005-3, p. 47-55.

- Cf. Notice by Brigitte Roux in Fravalo Fabienne (ed.). Les arts décoratifs (I). Sculptures, émaux, majoliques et tapisseries, Geneva, Fondation Gandur pour l’Art & Milan, 5 Continents Edition, 2020, p. 142-143.

- Tomasi Michele. “L’art multiplié: matériaux et problèmes pour une reflexion” in Michele Tomasi (ed.) and Sabine Utz (coll.), L’art multiplié. Production de masse, en série, pour le marché dans les arts entre Moyen Âge et Renaissance. Rome: Viella, 2011, p. 14.

- Cf. Burek Michaela. Der Fiesole-Altar im Domschatz zu Hildesheim. Untersuchungen zur Technologie von Intarsien und Malerei des Quattrocento. Stuttgart, 1989.

- The restoration report by Juliette Levy in 2017 also notes the presence of a repair on the upper part of the lid, based on the aspect of the bone and horn rods. The wooden rods, lock, and various marquetry elements are believed to have been posterior to the creation of the plates.

- Williamson Paul and Davies Glyn. Victoria and Albert Museum. Medieval Ivory Carvings 1200-1550, vol. II. London: V&A Publishing, 2014, p. 836-837 & 848-849.

- Tomasi Michele. “Baldassare Ubriachi, le maître, le public”, p. 57.

- Lett Didier. “Famille et relations émotionnelles” in Alain Corbin, Jean-Jacques Courtine & Georges Vigarello (ed.), Histoire des émotions, vol. 1: De l’Antiquité aux Lumières. Paris: Seuil, 2016.

- Bayer Andrea. “Introduction” in Andrea Bayer (ed.), Art and Love in Renaissance Italy, exhibition catalogue [New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 11.08.2008-16.02.2009; Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, 15.03-14.06.2009], New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art & New Haven/London, Yale University Press, 2008, p. 3-7.

- Musacchio Jacqueline Marie, ibid. p. 107-110.

- Lurati Patricia. Doni d’amore. Donne e rituali nel Rinascimento, exhibition catalogue [Rancate, Pinacoteca cantonale Giovanni Züst, 12.10.2014-11.01.2015], Silvana Editoriale, 2014, p. 56.

- Ibid.

- Tomasi Michele, Monumenti d’avorio.

Bibliography

Bayer Andrea (ed.), Art and Love in Renaissance Italy. Exhibition catalogue [New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 11.08.2008-16.02.2009; Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, 15.03-14.06.2009], New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and New Haven/London, Yale University Press, 2008.

Burek Michaela. Der Fiesole-Altar im Domschatz zu Hildesheim. Untersuchungen zur Technologie von Intarsien und Malerei des Quattrocento. Stuttgart, 1989.

Corbin Alain, Courtine Jean-Jacques and Vigarello Georges (ed.). Histoire des émotions, vol. 1: De l’Antiquité aux Lumières. Paris: Seuil, 2016.

Fravalo Fabienne (ed.). Les arts décoratifs (I). Sculptures, émaux, majoliques et tapisseries. Geneva: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art & Milan, 5 Continents Edition, 2020.

Lurati Patricia. Doni d’amore. Donne e rituali nel Rinascimento. Exhibition catalogue [Rancate, Pinacoteca cantonale Giovanni Züst, 12.10.2014-11.01.2015], Silvana Editoriale, 2014.

Tomasi Michele. “Baldassare Ubriachi, le maître, le public” in Revue de l’art, no. 34, 2001-4, p. 51-60.

Tomasi Michele. Monumenti d’avorio. I dossali degli Embriachi e i loro committenti. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, & Paris, INHA, 2010 (French summary: p. 329-369).

Tomasi Michele. “Le retable des Embriachi du musée du Louvre: datation, fonction, destination, iconographie” in La revue des musées de France. Revue du Louvre, 2005-3, p. 47-55.

Tomasi Michele (ed.) and Utz Sabine (coll.). L’art multiplié. Production de masse, en série, pour le marché dans les arts entre Moyen Âge et Renaissance. Rome: Viella, 2011.

Vigarello Georges; Lobstein Dominique; Courtine Jean-Jacques; Van Wijland Jérôme, Le Théâtre des émotions. Exhibition catalogue [Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet, 13.04.2022-21.08.2022], Paris, Hazan, 2022.

Williamson Paul and Davies Glyn. Victoria and Albert Museum. Medieval Ivory Carvings 1200-1550, vol. II, London: V&A Publishing, 2014.