March 2024 Ethnology

A giant from the terrible Solomons

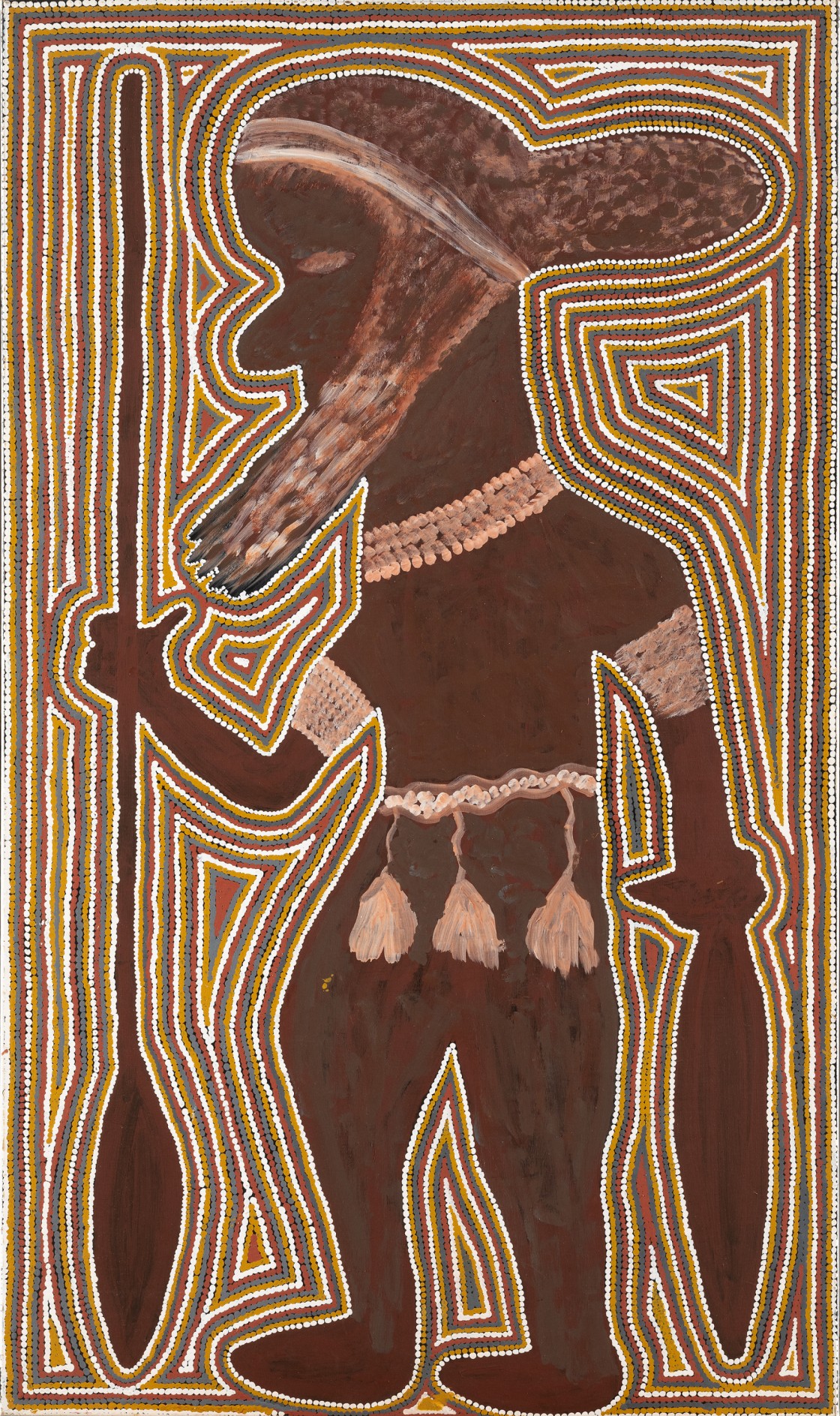

The exhibition High Five! held at the Fondation Opale in Lens (Valais) until mid-April highlights works of Australian Indigenous art from the collection of Bérengère Primat, mirrored with the artistic choices of 26 figures from the Swiss cultural scene. Jean Claude Gandur chose to bring together the painting of Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula titled My Father, the Mitukatjirri Warrior (fig. 1) and a huge house post from the Solomon Islands carved in the shape of an Ataro, thus giving pride of place to the role of the ancestor1.

See the artwork in the collectionRidge post

Melanesia, Solomon Islands, Makira province, Owa Raha, Gupuna village, late 19th century

Wood

274 x 58 x 50 cm

FGA-ETH-OC-0082

Provenance

Photographed by Martin Johnson in 1908, in situ

Photographed by Eugen Paravicini in 1927-1928 in the plantation of Heinrich Küper at Gupuna, Owa Raha

Photographed in 1933 by Hugo Bernatzik

Brought to Europe by the company Burns, Philps and co

Galerie Ernest Ascher, Paris (1935?)

Étude Charles Ratton, Paris, in 1936

Étude Guy Ladrière, Paris

Acquired 02.07.2022

"The Terrible Solomons"

It is with these rather unappealing words that Jack London referred to these islands, where he finished – while suffering from several illnesses – a sailing adventure in the South Seas started in 1907. We will be dealing with two islands of the south-east of this archipelago, which consists of more than 900 (fig. 2): Makira, called San Cristobal by the Spanish who discovered it in 1568, and its small satellite Owa Raha, also known as Santa Ana (or Santa Anna). These islands pertain to the Melanesian culture, unlike others, which are of Polynesian or Papuan culture. Owa Raha is closely linked to the name of Heinrich (or Henry) Küper, the first owner of the carved post discussed here. A deserting officer of the German navy, Heinrich Küper first settled as a plantation owner in Makira. But it is in the village of Gupuna, at Owa Raha, that he finally moved, married a rich woman2 and soon became a respected patriarch who would sometimes use violence to reach his goals. This granted him the title of arafa (“Great”)3. In 1935, he guided through the Solomon Islands the members of the expedition La Korrigane (1934-1936), who were looking for objects for the Musée de l’Homme in Paris4. Although a controversial figure, he was sincerely interested in the defence of the Solomon culture, and sometimes performed the work of an ethnologist5. Along with him, one can also mention the ethnologist and botanist Eugen Paravicini, who stayed on Owa Raha in 1927-1928, and the anthropologist Hugo Bernatzik (“Doktor Hugo”), who was a guest of Heinrich Küper during his stay on the island with his wife in 1932-1933.

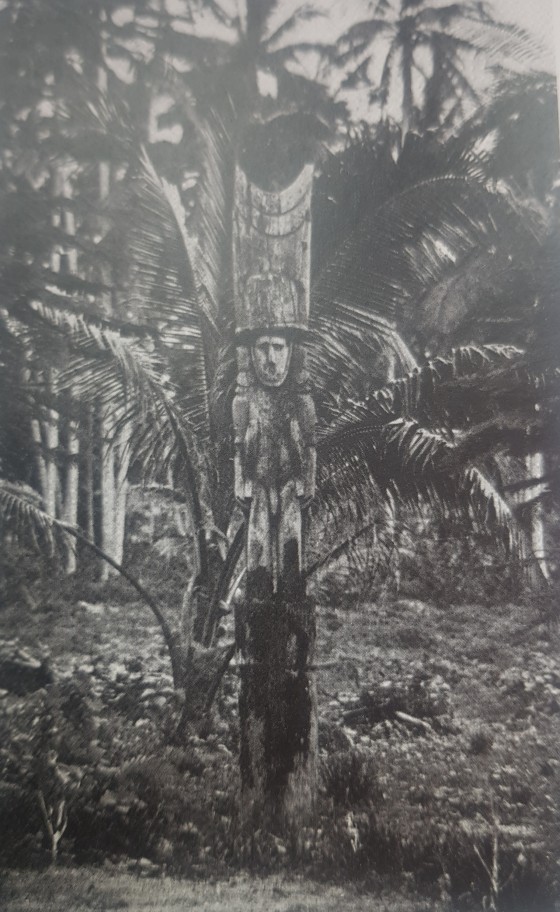

A giant seen from the Snark

Few objects are as documented as this post, which enables us to trace a rather precise record of its history. Honour where honour is due: in this case, we are to thank the ancestors or forefathers of ethnology. The post already appears, in its initial context of use, on a unique photograph taken on 30 June 1908 by Jack London or his crewman Martin Johnson from their boat, the Snark (fig. 3)6. The photograph shows the huge post, the top of which is more than 5 meters above ground, and which supports the ridge beam of the aofa apuna (or Kastom house in pidgin, in other words the ceremonial house) of Gupuna7, a village where Heinrich Küper settled a few years later. On the upper part of the post, one can recognize the large statue of a man with its unmissable colonial helmet.

The memories of Malakai and the photographs of ethnologists

A testimony recorded in the 1970s by the ethnologist Doris Byer (daughter of Hugo Bernatzik) from Malakai, a resident of Gupuna born in 1901, tells us that after the evangelisation of the island, the locals had turned away from the ancient places of worship, and that the abandoned aofa had fallen into ruins. Heinrich Küper had then brought to his property the only post still standing, where it was photographed by Eugen Paravicini in 1927-1928 (fig. 4), then in 1932 by Hugo Bernatzik (fig. 5); in the meantime, our giant had been shortened by more than 2 meters. It is in this state that it was embarked on the ship of Burns Philps and co. It then entered the collection of the dealer Ernest Ascher in Paris, who sold it to Charles Ratton. It was notably photographed in the latter’s garden in Paris for the Exposition surréaliste d’objets (Surrealist exhibition of objects) which took place in 1936, thus finding its place in a Western world which was then discovering the art of Oceania (fig. 6)8.

Ridge posts from Owa Raha, Makira and Uji

Let us replace this statue in its original geographic context: that of the islands of Makira, Owa Raha and Uji at the time of the first travellers, in the late 19th and early 20th century. Written records, photographs and other carved pieces in museums show the importance of this monumental statuary made in a tall tree trunk. In most cases, they show a nearly always male character, naked but with body ornaments, perched on a column with a smooth shaft. They were used to support the roof of ceremonial houses, hence their rounded notch at the top, which once held the horizontal beam. There were usually three of these sculpted posts on the façade side, a tall one in the middle and two shorter ones on each side. And when there were four of them lengthwise, no less than twelve posts would support the roof of one aofa (fig. 7)9. However, the one at Gupuna was more modest, as the 1908 photograph shows. A boathouse for war pirogues, a shelter for reliquaries containing the skulls of manhunt victims, but also a hotspot for male initiation10, the aofa was taboo and its access strictly forbidden to women.

The radiance of a superior being atop the post

The photograph taken from the Snark is interesting in many ways, notably because it shows the post in its original state, which would otherwise be completely unknown today. The statue and its circular base were painted: black diamonds on a white background around the base, white for the man’s body, black for the two large fishes he is holding in his hands, with an appealing black-and-white contrast typical of the production of these islands. The man is bare, but is wearing a colonial helmet, from which two strands of curly hair emerge (fig. 8). The helmet is adorned on its sides with long, thin fishes depicted with their head down (perhaps needlefishes?) and fastened with a broad chinstrap. It is prolonged by a high rectangular plaque, the top of which is decorated with two parallel crescents, the upper one following the curve of the notched rim.

The different jewellery pieces all reproduce in wood the ornaments of Makira11: broad ear ornaments made of a disc with feathers or petals attached, and nosering in the shape of a “shoal of fishes” (parapara ni’e), often made of mother-of-pearl (fig. 9)12. In the dress of Makira, the large pectoral is an openwork pattern of tortoiseshell affixed to a shell disc. As for the armbands, they imitate rings sculpted in large conus shells and worn by the distinguished residents of Makira and Malaita13. Their common feature is that they are white and very shiny, as they were made from polished shells, as if to highlight the uncommon qualities of the bearer; the colonial helmet probably had the same symbolic function. It is with a coat of the British navy and a Western hat that the king of the island of Uji had welcomed Count Festetics de Tolna during the latter’s trip in Oceania from 1893 to 190114.

The artist of Gupuna

Concerning the sculpture of posts, each village had its experts: in Santa Ana, some of these sculptors were still active in the 1960s15. The artist of Gupuna, who was active around the end of the 19th century, remains anonymous, but he must have produced at least another statue, very similar and also very tall, collected in the same village of Gupuna by Eugen Paravicini for the ethnography museum of Basel (fig. 10)16. And what an artist! A feeling for symmetry and volumes, the rendering of motion, balance of proportions, a care for detail and harmony of shapes are as many features displayed by these two monumental and spectacular pieces, made with tools of stone and shell. Two statues which were separated from their shaft before they were sent abroad.

However, our two giants differ in some details. First the hat: a British colonial helmet for the statue of the Fondation, and a shorter pointed helmet with cheek guards for the Basel statue. The carved plaque above the helmet is adorned on each side by two vertically arranged flying frigate birds facing each other, and two parallel crescents at the top. On the Basel statue, the two long fishes depicted on the sides of the rectangular plaque are replaced by two wavy snakes, and a shark is apparently leaping from the water to reach the rear of the legs of the figure (fig. 11). Finally, he is holding with his two hands a dance mace used during the initiation of the youth17.

The Ataro

These two posts are anthropomorphic depictions of the Ataro, the spirits of the depth of the sea. These ambivalent beings, sometimes dangerous, sometimes benevolent, could throw needlefishes like arrows towards boats, but they also attracted shoals of fishes towards the coasts where fishermen would catch them, notably the precious bonitos. These spirits of the depth, who also mastered rainbows and diluvian rains, had to be flattered18. Depicted atop the ridge posts and named individually by name, the Ataro protected the initiated youth and the men of the community, notably by favouring the abundance of fish. On the island of Owa Raha, any phenomenon of sun- or moonlight glittering on the scales of bonitos, of mirroring on the water, of shimmering, glare or iridescence, was considered a sign of their supernatural presence19. The white ornaments and the helmets on their statues were as many details expressing their supernatural nature.

A role of supplier and protector of the community which the warrior with white armbands Mitukatjirri would not have disavowed.

Dr Isabelle Tassignon

Curator of the Ethnology collection

Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, March 2024

Translation: Dr Pierre Meyrat

Notes and references

- I thank Sandrine Ladrière for her research in the archive of Charles Ratton, and Alia Oezvegyi of the Museum der Kulturen Basel.

- At Makira, Santa Isabel and Guadalcanal, the transfer of goods occurred in the matrilinear line: Lawrence, The Naturalist, p. 246.

- Revolon, “Heinrich Küper”, pass.; see also Guy Bounoure, in Falgayrettes-Leveau, Van Cutsem-Vanderstraete, L’art d’être un homme, p. 190.

- Christian Coiffier, in Mélandri, Revolon, L’éclat des ombres, p. 59.

- For instance by publishing an article on female tattooing (Küper, “Tapitapi”, pass.) or by organizing in 1942 the last initiation at Gupuna, during which his son Geoffrey was initiatied: Mead, “The Last initiation”, pass.

- The photograph was published by Viotte, Pourtal-Sourrieu, Jack London, p. 150, but not identified.

- Johnson, Through the South Seas, p. 294; on this sojourn: Viotte, Pourtal-Sourrieu, Jack London, p. 150.

- Peltier, “L’art océanien”, p. 271-282.

- Davenport, “Sculpture”, p. 14.

- Mélandri, Revolon, “Poteaux de maison cérémonielle”, p. 170-171.

- Burt, Body Ornaments, p. 138-139.

- An ornament described by the first travellers in the 19th century. It covered the mouth, often red-stained from chewing betel, and one had to raise it with the left hand while eating: Guy Bounoure, in Falgayrettes-Leveau, Van Cutsem-Vanderstraete, L’art d’être un homme, p. 188.

- Burt, Body Ornaments, pass.

- Festetics de Tolna, Chez les Cannibales, p. 297-301.

- Davenport, “Sculpture”, p. 8-9 and p. 13-14.

- Basel, Museum der Kulturen, inv. Vb 7446. The preserved face of another statue seen on a blog could be of the same hand: https://thesublimeblog.org/2020/11/02/making-faces-the-expressiveness-of-oceanic-tribal-art/

- Bernatzik, Owa Raha, p. 25, fig. 22 (similar object held by a similar figure, in the aofa of Natagera).

- Scott, “La pêche à la bonite”, p. 169; Peltier, “Poteau de maison”, p. 64.

- Revolon, “Les couleurs de la métamorphose”, p. 146-151; Revolon, “Iridescence as Affordance”, pass.

Bibliography

Former publications

Paravicini, Eugen, Reisen in den britischen Salomonen, Frauenfeld and Leipzig, 1931, p. 146-147 and pl. 55.

Exposition surréaliste d’objets, 1936.

Falgayrettes-Leveau, Christiane, Van Cutsem-Vanderstraete, Anne (eds), L’art d’être un homme. Afrique, Océanie, Paris, Musée Dapper, 2009, p. 190-191.

Peltier, Philippe, “Poteau de maison des hommes, îles Salomon”, in Dagen, Philippe, Murphy, Maureen (eds), Charles Ratton. L’invention des arts « primitifs », exhibition catalogue, Quai Branly, 25.06 – 22.09.2013, Paris, Somogy, 2013, p. 62-63.

Mélandri, Magali, Revolon, Sandra, “Poteaux de maison cérémonielle”, in Mélandri, Magali, Revolon, Sandra (eds), L’éclat des ombres. L’art en noir et blanc des Îles Salomon, exhibition catalogue, Quai Branly, 18.11.2014-01.02.2015, Paris, Somogy, 2015, p. 170-171.

High Five!, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Opale, 17.12.2023-14-04.2024, Fondation Opale, Lens, 2023, p. 53 and p. 129-133.

Bibliography

Bernatzik, Hugo, Owa Raha, Vienne-Zurich-Prague, Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1936.

Brunt, Peter, Thomas, Nicholas (dir.), Océanie [catalogue d’exposition Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris 12.03 – 07.07.2020], Fonds Mercator, Bruxelles, 2018.

Burt, Ben, Body Ornaments of Malaita, Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 2009.

Byer, Doris, Die Grosse Insel. Südpazifische Lebensgeschichten. Autobiographische Berichte aus dem südöstlichen Salomon-Archipel seit 1914, Vienne, Verlag-Böhlau, 1996.

Davenport, William Hunt, “Sculpture of the Eastern Solomons”, Expedition, 1968, p. 4-25.

Exposition surréaliste d’objets, Galerie Charles Ratton, Paris, 1936.

Falgayrettes-Leveau, Christiane, Van Cutsem-Vanderstraete, Anne (eds), L’art d’être un homme. Afrique, Océanie, Paris, Musée Dapper, 2009.

Festetics de Tolna, Rodolphe, Chez les Cannibales. Huit ans de croisière dans l’océan Pacifique à bord du yacht « Le Tolna », Paris, Plon, 1903.

Johnson, Martin, Through the South Seas with Jack London, London, T. Werner Laurie Ltd, 1913.

Küper, Heinrich, “Tapitapi or the tattooing of females on Santa Ana and Santa Catalina (Solomon Group)”, Journal of the Polynesian Society, 35, 1926, p. 1-5.

Lawrence, David Russell, The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’. Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific, Canberra, Anu Press, 2014.

Mead, Sydney Moko, “The Last Initiation Ceremony at Gupuna Santa Ana, Eastern Salomon Islands”, Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum, 10, 1973, p. 69-95.

Mélandri, Magali, Revolon, Sandra (dir.), L’éclat des ombres, l’art en noir et blanc des Îles Salomon [catalogue d’exposition Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, 18.11.2014-01.02.2015], Paris, Somogy éditions d’Art, 2014.

Mélandri, Magali, Revolon, Sandra, “Poteaux de maison cérémonielle”, in Mélandri, Revolon, L’éclat des ombres, p. 170-171.

Paravicini, Eugen, Reisen in den britischen Salomonen, Frauenfeld et Leipzig, 1931.

Peltier, Philippe, “L’art océanien entre les deux guerres : expositions et vision occidentale”, Journal de la Société des océanistes, 35, 1979, p. 271-282.

Peltier, Philippe, “Poteau de maison des hommes, îles Salomon”, in Charles Ratton. L’invention des arts « primitifs » [catalogue d’exposition Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, 25.06 – 22.09.2013], Paris, Somogy, 2013, p. 170.

Revolon, Sandra, “Les couleurs de la métamorphose. La lumière comme mode d’action sur le monde”, in Mélandri, Revolon, L’éclat des ombres, p. 146-151.

Revolon, Sandra, “Heinrich Küper : le Blanc dont on parle à mi-voix”, Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 116, 2003, p. 65-75.