Read, watch and play

ArtCase

Developed to mark the 15th anniversary of the Fondation Gandur pour l'Art and structured around three themes — dressing, dwelling, and travelling — ArtCase offers a reimagined version of the classic game of snakes and ladders. Blending a race against time with the exploration of artworks and objects from the Fondation’s collections, the game invites players to engage with cultural heritage in an interactive and playful way.

Dressing

A meeting point between bodies and textile materials, the art of dressing — and of dressing oneself — has for millennia constituted a fundamental human practice, serving in turn as protection, tool, social marker, means of identification, belonging, or distinction.

In this first chapter of ArtCase, the snakes and ladders-style game conceived by the Fondation Gandur pour l'Art around its collections, clothing appears both as a tangible object and as a depicted element in painting, sculpture, or photography. It transcends time periods and geographic regions, giving rise to multiple narratives which, though diverse and far-reaching, are united by a shared purpose: to cloak human beings and their representations in a veil of dignity.

Abstract from Olivia Fahmy's introduction

Il mimo [Le Mime]

Artistic Foot(wear) [Pied(chaussure) artistique]

Umberto MARIANI

Il mimo [Le Mime]

November 1969

Acrylic on canvas

91.9 x 64.6 cm

FGA-BA-MARIA-0001

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Morin © Umberto Mariani

Allen JONES

Artistic Foot(wear) [Pied(chaussure) artistique]

1966

Oil on canvas with a shelving in formica and a heel in varnished leather

93 x 92.3 cm x 10.7 cm

FGA-BA-JONES-0001

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Morin © All rights reserved

Links between these artworks

Did Umberto Mariani’s gloves send you sliding down to the sheer stockings adorning Allen Jones’s feminine silhouette? It was inevitable. Landing on square 3 offers an opportunity to delve into the societal shifts surrounding the status of women in the 1960s.

As the structure of the traditional family began to evolve and women gained greater autonomy, representations of the female body reflected this emancipation. In Il mimo (The Mime), Umberto Mariani focuses on an aesthetic exploration of fabric, enhancing the elegance of gloved hands. Allen Jones, meanwhile, captures this transformation in Artistic Foot(wear) by highlighting the allure associated with the modern woman. Silhouettes were liberated, and clothing adapted to a new way of life.

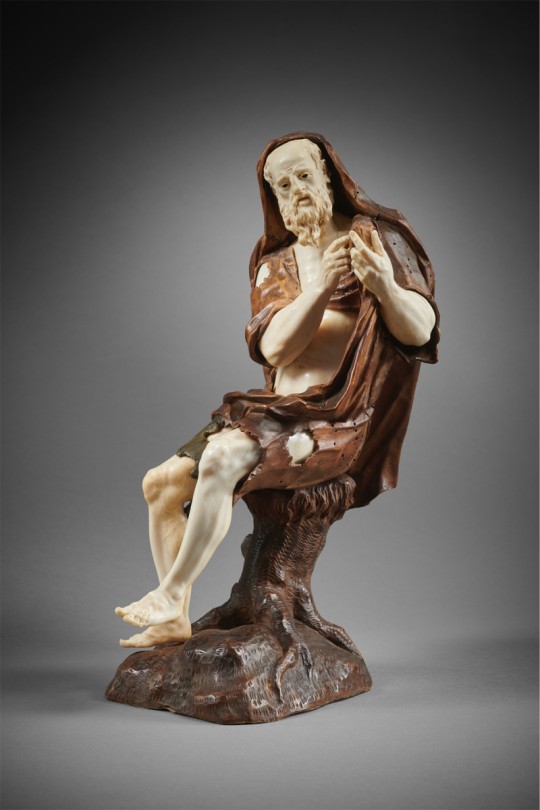

Sitting beggar

The Charity of Saint Martin

Matthias KOLB, attributed to

Sitting beggar

Circa 1730

Ivory, limewood, and glass (eyes)

30 x 14.8 x 17.4 cm

FGA-AD-BA-0015

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

The Charity of Saint Martin

1st quarter 16th century

83.5 x 64 x 33 cm

FGA-AD-BA-0184

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Links between these artworks

From a beggar in ragged clothing, you have risen all the way to square 53 — all thanks to the charity of Saint Martin, who offers his cloak to a man in need.

These two works have been brought into dialogue for their shared reflection on the primary function of clothing: to cover and protect us from the cold and the elements. By drawing attention to exposed and vulnerable bodies, they serve as a reminder of the fundamental human need for clothing — and the enduring importance of solidarity.

Model of an offering-bearer

Composite sculpture of said "princess"

Model of an offering-bearer

1st quarter 2nd millenium BC

Polychromous wood

36 x 12.4 x 5.5 cm

FGA-ARCH-EG-0198

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Longchamp

Composite sculpture of said "princess"

Late 3rd millenium - early 2nd millenium BC

Chlorite and calcite

23 x 9.5 x 13 cm

FGA-ARCH-BA-0023

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Longchamp

Links between these artworks

Dressed in a simple white robe, an Egyptian offering-bearer has extended the ladder to a millennia-old Central Asian princess adorned with a heavy, patterned textile. On square 41, reflect on clothing as a means of identification and belonging. Here, attire—whether through its simplicity or its intricacy—serves to delineate the roles of these two women within their respective societies.

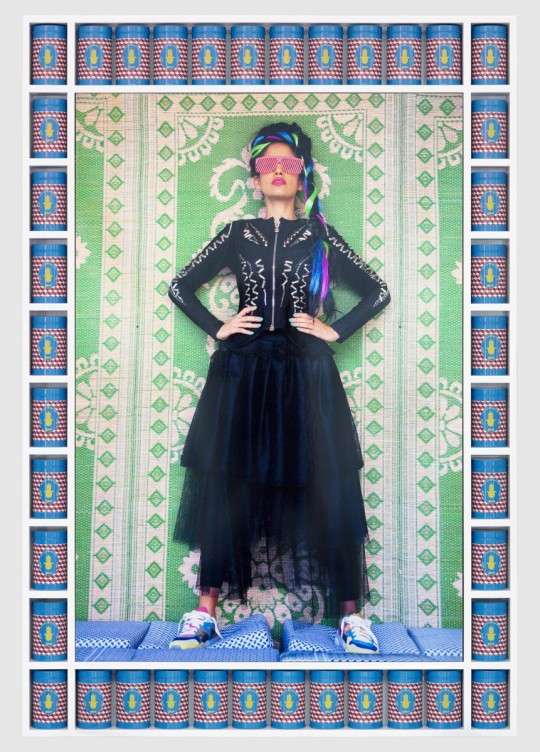

Statuette of Aphrodite fastening her necklace

Her Majesty, Queen Sophie

Statuette of Aphrodite fastening her necklace

Mid-1st century CE

Hollow cast terracotta

36 x 14.5 x 6.9 cm

FGA-ARCH-RA-0198

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Longchamp

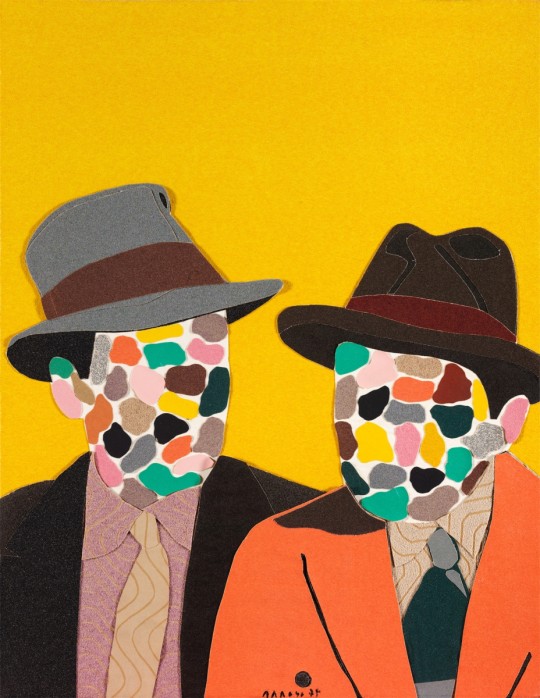

Mary SIBANDE

Her Majesty, Queen Sophie

2010

Photography, pigmentary print

Edition of 10 + 3AP

Non-numbered artist proof

104 x 69 cm

FGA-ACAD-SIBAN-0001

© Mary Sibande

Links between these artworks

An ancient goddess, draped in a wet-look pleated robe, may have made you leap forward a few squares. If that’s the case, you’re likely standing on square 36, where the work of Mary Sibande reveals a domestic worker in majesty.

These two works have been brought together for their exploration of pleating, a technique used by artisans and artists alike to signify the refinement and quality of a garment —offering, in turn, insights into the person wearing it. The pleats of the garment that clung unmistakably to the body of the ancient goddess to highlight her eroticism are expanded in the work Her Majesty, Queen Sophie to evoke the opulence of a Victorian gown, the kind associated with royalty. Here, that grandeur is used to reveal the figure of the domestic worker — embodied by the artist herself through her alter ego, Sophie, the daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter of women assigned to housework. The garment thus becomes a powerful symbol, used to address the power dynamics embedded in South Africa’s colonial and apartheid history.

Dwelling

From the culinary practices of Ancient Egypt to household maintenance, from the ceremonial salons of the Grand Siècle to post-war and contemporary interiors, the home offers a rich panorama of the elements and activities that define domestic life across the ages.

In this second chapter of ArtCase, a reimagined version of the game of snakes and ladders, the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art invites you to explore the art of inhabiting space in all its dimensions. Inviting reflection on the interplay between ornament and utility, display and intimacy, entertainment and the management of everyday life, the works brought together here evoke both the comforts of the home and the broader societal questions surrounding the division of roles. They offer insights—at times playfully—into the ways in which humans construct and lay claim to their surroundings, which, over the centuries, have become a mirror of their inhabitants.

Abstract of Fabienne Fravalo's introduction

Je passe, vous repasserez II

Premier jour de lessive

Ivan MESSAC

Je passe, vous repasserez II

June 1968

Chinese ink on paper

50.1 x 47.9 cm

FGA-BA-MESSI-0002

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Morin © 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich

Jourdan TCHOFFO KUETE

Premier jour de lessive

2023

Acrylique sur toile

150.4 x 150.4 cm

FGA-ACAD-TCHOF-0004

© Jourdan Tchoffo Kuete © Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: Lucas Olivet

Links between these artworks

Just as you were about to break free from household chores, you’ve found yourself back at day one of doing the laundry… How disheartening!

Will women’s emancipation from domestic chores be an eternal struggle? Fifty-five years after May ’68 and Ivan Messac’s mischievous India-ink drawing Je passe, vous repasserez (“I pass through, you’ll iron.”), Jourdan Tchoffo Kuete’s large canvas poses this question with irony. In a laundry room where oversized household appliances occupy spaces usually devoted to pieces of luxury furniture, a woman lowers her gaze toward an enormous heap of laundry spilling out of a basket. Through a vivid, almost acidic palette that creates a sense of timelessness, Premier jour de lessive (“First Day of Laundry”) subtly invites us to reconsider how these household practices have evolved since the postwar boom and the era of globalization.

Table à jeux multiples

Jeux de dame

Guillaume KEMP

Table with multiple games

3rd quarter 18th century

Structure in fir and oak; veneering in rosewood, stained maple (‘tobacco wood’), satinwood, green-stained hornbeam, kingwood, holly, amaranth, ebony, ivory, and green-stained ivory; gilt bronze; modern felt.

FGA-AD-MOBI-0063

Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Luzamba Musiri ZEMBA

Jeux de dame

2020

Oil on canvas

139.4 x 159 cm

FGA-ACAD-LUZAM-0006

© Luzamba Musiri Zemba © Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: Lucas Olivet

Links between these artworks

Enough admiring — we’re waiting for you for a wild game of draughts!

In the 18th century, board games were one of the favourite pastimes of the European elite during social gatherings. To make this activity more enjoyable and to integrate it harmoniously into the elegant interiors of aristocrats and wealthy financiers, master cabinetmakers competed in ingenuity. The games table attributed to Guillaume Kemp, for instance, reveals a game of trictrac (a precursor to backgammon) beneath an upper lottery board, while a side flap conceals a set of six interchangeable trays fitted with double-sided engraved boards. Two and a half centuries later, the work of Luzamba Musiri Zemba affirms the enduring and universal appeal of draughts, whose origins can be traced back to Ancient Egypt with the game of senet.

Fleurs blanches et jaunes

Vase crowned with fruits

Nicolas de STAËL

Fleurs blanches et jaunes

1953

Oil on canvas

130 x 89 cm

FGA-BA-STAEL-0003

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Sandra Pointet © 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich

Giovanni DELLA ROBBIA, workshop of

Vase crowned with fruits

1st quarter 16th century

Enamel

37 x 26 x 24 cm

FGA-AD-OBJ-0073

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Links between these artworks

Oops! You let yourself be tempted by one bouquet too many… Time to indulge in even more extravagance!

Endowed with symbolic meaning linked to their olfactory properties, flowers have been associated since Antiquity with religious and funerary rituals, as well as with the decoration of homes. From the Renaissance onwards, a true floral art developed, intended to enhance the refinement of royal and aristocratic residences. Vases adorned with artificial flowers and fruits in faience, produced during the same period by the della Robbia workshop, offered a particularly luxurious and lasting equivalent. At the end of the 20th century, Fleurs blanches et jaunes by Nicolas de Staël once again evokes this now familiar decorative element: the bouquet.

Lamp decorated with heads of Minerva and dolphins

Pair of wall lights

Lamp decorated with heads of Minerva and dolphins

1st century CE

Bronze

21.7 x 26 x 26 cm

FGA-ARCH-RA-0205

© Photographiquc credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Longchamp

Antoine LELIEVRE

Pair of wall lights

mid-18th century

Gilded bronze

63 x 42 x 19.3 cm

FGA-AD-OBJ-0006 a+b

© Photographic credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Links between these artworks

From the 1st century AD to the mid-18th century, you certainly came a long way — yet the sources of lighting hardly changed at all!

If the home serves as a place of refuge, especially at night, then lighting it adds to both its comfort and, indeed, its very livability. Until electricity appeared in the late 19th century, fire was the primary source of light. The design of objects to hold the glowing material sparked the creativity of artisans: lamps were often crafted as genuine works of art, adding charm to interiors even when unlit.

Travelling

Humankind has been travelling ever since curiosity and the urge to explore have set its feet in motion. As walking has its limits, travellers first harnessed the strength of animals before exploiting that of machines. From then on, they moved on horseback, by camel, in carriages, by boat, or by airplane, with each advance in transport technology reducing the time needed to traverse distances. Today, in the digital age, distance is no longer an obstacle to discovering the world, which can now be explored at the click of a button.

The third chapter of ArtCase presents artworks that evoke the long history of travel across time and space. They also reflect the contrasting stakes and motivations of travellers, driven by curiosity, the spirit of conquest, or the dream of a better life.

Abstract of Bertrand Dumas' introduction

Chest bearing the arms of the Prince of Condé

Pack camel

Chest bearing the arms of the Prince of Condé

Circa 1700

Spruce-wood frame, partially gilded leather, iron, and domino paper

30 x 60 x 30 cm

FGA-AD-OBJ-0095

© Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Pack camel

VIIe - Xe siècle après J.-C.

Terre cuite polychrome

43.5 x 26.5 x 49.5 cm

FGA-ETH-AS-0017

© Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Links between these artworks

If you’ve landed on square 186, you'll have realised by now: to travel well, one must first be properly equipped!

Among the objects produced to accompany travellers are chests, such as the leather-covered example bearing on its lid the arms of the House of Condé. The refinement of its gilded decoration, executed in the early eighteenth century, attests to the prestige of its patron. Once personal effects have been stowed away, attention must then be given to one’s mount, particularly when it is heavily laden, as illustrated by this terracotta pack camel from China’s Tang dynasty (678–907 CE). This type of figurine, placed in tombs, accompanied the deceased on their final journey into the afterlife, evoking the society that surrounded them during their lifetime. Camelids were then numerous around the markets of major Chinese cities from which the Silk Road departed, a commercial route linking Chang’an to Constantinople.

Exodus n° 1

Untitled

Karel APPEL

Exodus n° 1

1951

Oil, gouache, coloured pencil, and collage on kraft paper mounted on canvas

100.1 x 65.3 cm

FGA-BA-APPEL-0006

© Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: André Morin © 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich

ABOUDIA

Untitled

2017

Oil pastels and acrylic on canvas

122 x 183 cm

FGA-ACAD-ABOUD-0003

© Abdoulaye Diarrassouba © Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Lucas Olivet © 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich

Links between these artworks

You have reached square 165: a moment to reflect on the issue of exile.

In a small wheeled cart are piled toys and stuffed animals. One can sense that these belongings were hastily gathered by a child, collecting what was most precious to them—much like the families who, fleeing the advance of the Third Reich’s troops, loaded their possessions onto carts and set out across Europe. This collage by Karel Appel, entitled Exodus, also bears the name of a famous ship that, in 1947, attempted to reach the future State of Israel carrying 450 survivors of the Jewish genocide. This poignant episode of postwar mass migration resonates with Aboudia’s painting, created in 2017, which depicts another boat carrying migrants. Among the inscriptions rendered in capital letters on the black background of his work are the names of countries and cities—destinations that the passengers, forced into exile, hope to reach.

Bureau de pente

Métasphère (II)

Jacques DUBOIS

Bureau de pente

Circa 1750 - 1760

Oak and spruce frame, fruitwood (alder) veneer with black varnish, Japanese lacquer, European varnish, gilded bronze, leather, and (modern) lacquer

88 x 117.3 x 52 cm

FGA-AD-MOBI-0013

© Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Jean DEGOTTEX

Métasphère (II)

25 november 1965

Acrylic on canvas

214 x 129 cm

FGA-BA-DEGOT-0005

© Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Sandra Pointet © 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich

Links between these artworks

Oh no, you’ve landed back on square 152… Time to delve even deeper into centuries of cultural exchange!

European artists’ interest in the Far East intensified in the eighteenth century with the opening of new trade routes. A testament to the encounter between Europe and Asia, the bureau de pente by the cabinetmaker Jean Dubois incorporates into its decoration earlier lacquer panels reused from cabinets or screens imported from China or Japan. Two centuries later, in 1965, the artist Jean Degottex likewise turned his gaze towards the Far East, this time drawn by the purity of Chinese calligraphy, which he discovered in Comments on Painting by the monk Shitao. The first chapter of this treatise, composed in the early eighteenth century, is entitled The Single Brushstroke. Jean Degottex appears to have drawn direct inspiration from it in executing the large vertical sign that runs through the painting Métasphère (II).

Saint James the Greater

Miki Liste

Saint James the Greater

Circa 1470 - 1500

Oak wood

140 x 41 x 30 cm

FGA-AD-BA-0014

© Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Geneva. Photographer: Thierry Ollivier

Luzamba Musiri ZEMBA

Miki Liste

2019

Oil on canvas

130 x 89 cm

FGA-ACAD-LUZAM-0002

© Luzamba Musiri Zemba © Photo credit: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva. Photographer: Lucas Olivet

Links between these artworks

You have set out on a pilgrimage under the protection of Saint James! Welcome to square 181.

Carved from a solid oak trunk in Flanders at the end of the fifteenth century, the figure of Saint James the Greater is identifiable by his attributes: the book marks him as an apostle, while the staff, satchel, and hat adorned with a scallop shell signify his role as the patron saint of pilgrims, venerated by Catholics at his tomb in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. From Galicia, Spain, Artcase transports us to the Congo, where we encounter an elegant urbanite whose attire and accessories identify him as a member of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes—better known by its acronym, S.A.P.E. His fuchsia tie with white crosshatch, paired with a pink shirt coordinated with the pocket square of his tailored jacket, marks him as a consummate dandy. Luzamba Musiri Zemba portrays him with his face concealed behind a visa, perhaps to suggest that the art of sape, as popular in Brazzaville as in Château Rouge, Paris, transcends borders.

Artworks in the game

Discover our newsletter

We just sent you a verification email. Please click the link in the email to complete the subscription process.

All rights reserved. Without authorization from ProLitteris, the reproduction and any use of the works other than individual and private consultation is prohibited.